Trees are a way of seeing

How Christopher Alexander saw a human way to build the future.

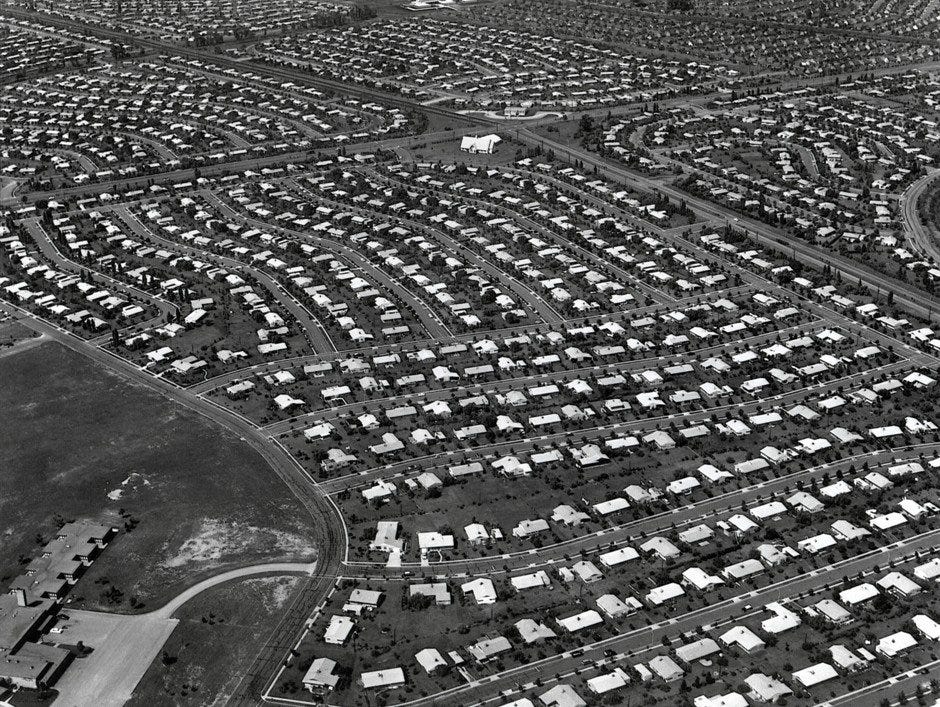

If you’re anything like me demographically, there’s a nonzero chance you grew up in a suburban environment similar to mine — a master-planned community. Orange County, CA overflows with such towns. The Levittowns of the postwar era typified these communities, which were built inexpensively and at scale without traditional urban infrastructure.

The notion of a “master plan” connotes a mental model of a town or city with manageable, discrete components. Such components might relate to one another, but in hierarchical and predictable ways. Mathematically, such a model of a city could be thought of as a “tree”.

Christopher Alexander was an architect and design theorist who caught on to this notion, making it a core piece of his thesis for his 1965 essay, “A City Is Not a Tree.” Alexander contrasts two different structures as mental models for cities — trees and semilattices. He writes:

Both the tree and the semilattice are ways of thinking about a how a large collections of many small systems goes to make up a large and complex system. More generally, they are both names for structures of sets. … When the elements of a set belong together because they operate or work together somehow, we call the set of elements a system.

That sounds fairly abstract, but he provides the reader with the concrete example of an actual street corner to illustrate his point. The intersection of Hearst and Euclid in Berkeley, CA, at the time of writing, included a drugstore, a traffic light, and a newsrack in the drugstore entrance. He writes:

When the light is red, people who are waiting to cross the street stand idly by the light; and since they have nothing to do, they look at the papers displayed on the newsrack which they can see from where they stand. Some of them just read the headlines, others actually buy a paper while they wait.

Despite it being 2024 rather than 1965, we can still see his point. (Tangentially, I’m writing this in the Notion app, and the spell checker does not recognize “newsrack”.) The individual elements of the street corner interact in an emergent way, forming a system. Other examples of urban systems that he gives include

…the set of particles which go to make up a building; the set of particles which go to make up a human body; the cars on the freeway, plus the people in them, plus the freeway they are driving on; two friends on the phone, plus the telephones they hold, plus the telephone line connecting them…

You get the idea. And for Alexander, these elements overlap in multiple interlocking ways, while all still being core elements of a city. It is unfathomably complex.

A tree, on the other hand, is comparatively structurally simple. According to Alexander, the mental model that many designers bring to urban planning is that of a tree, because the human mind innately tends toward simplification.

Alexander’s influence and insights aren’t limited to urban planning and architecture either — he’s very influential in the fields of computer science, design, and even religion. The fourth volume of his opus, The Nature of Order, veers into the realms of cosmology and human perception, arguing that human consciousness is “inextricably joined to the substrate of matter, present in all matter.” In his view, humans naturally build with the grain of the universe.

In my parish’s Sunday school class on sacred architecture, our teacher, Dr. Nathan Jennings, argued that this is partly why what we build often ends up looking like things we see in our nature. It’s not that there’s necessarily a conscious, deliberate parallel between, let’s say, the columns of a church and the trees in the woods that surround it, but simply that humans, being a part of nature and not something other than it, replicate the patterns of the natural world of which they are apart.

Dr. Jennings introduced the class to the work of Alexander as relevant to church architecture. He explained how Alexander attributes much of our modern malaise to a built environment that is distinctly at odds with a human way of being in the world — that, to paraphrase Dr. Jennings, maybe we’re so depressed because we spend most of our time in concrete boxes under fluorescent lights. Alexander deeply understood how the built environment affects people.

Alexander’s work sought to define architecture from “first principles”. He found the scientific positivism that was intellectually en vogue throughout his education was insufficient for formulating those first principles. Such an understanding even led him to see architecture as an attestation to the existence of God as a necessity of the universe. From Alexander’s work, we could infer that an inhuman built environment that is at odds with the grain of nature is anti-God, because it is a design contrary to the fundamental designs of nature, a nature that has God as the ground of its being. He departed from the strictly mechanistic and compartmentalized worldview that dominated the intellectual zeitgeist of his time. He became principally concerned with human healing and wholeness. You could say he exchanged his tree-like mental model for that of a semilattice.

His spiritual explication of architecture contained in it a critique of what he saw as the egocentric and deracinated theory and practice of architecture that was dominant in the twentieth century. He endured criticism and censure from colleagues. Nonetheless, he remained committed to the pursuit of the truth he perceived in nature. He writes that he was able “through contemplation of the whole, to emerge into the light of day with a view of things that is both visionary and empirical.” The visionary view is able to see the underlying, uniting patterns that the empirical gaze is inherently prevented from seeing.

But “visionary” also has another sense, of being able to envision the future. Thus, to build the future requires a visionary capability. Yes, one must also have empirical knowledge to manipulate and properly handle the world’s material. But because the empirical only measures what is, one must engage the visionary sense to perceive what could be. It requires looking at the connections, overlaps, and patterns that make up the world. It requires seeing things as a lattice, not a tree.